Erythropoietic Protoporphyria (EPP)

My early life was much like yours, painful exposure to the sun, nobody knew what I had, etc, etc. The fact that this was the late 1940s didn’t make a difference, either. EPP hadn’t even been discovered yet. Passed from doctor to doctor, various diagnoses were made: She’ll grow out of it when she reaches puberty, she’s just “acting out”, she’s missing a layer of her skin. The one I liked best was “if she gets a suntan, the symptoms will go away”. I don’t have to tell you THAT was a bad idea!

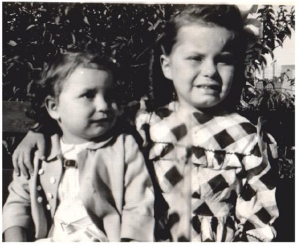

So, as the years went by, I learned to cope with my sun “allergy”, avoiding the sun, standing in the shade, wearing gloves, I’m sure you know the drill. The worst part, was when I was in grade school, we all had to line up in the schoolyard and march in the class at the beginning of the day and at each recess. Couldn’t get out of that, since I didn’t have a diagnosis, and schools weren’t that “disability friendly” in the 40s and 50s. I spent most of my childhood in some degree of pain. In those days, cameras didn’t have flash attachments, so we had to stand in the sun to get a good image. This photo of me and my little sister says it all.

I really think that those days gave me the experience of standing up to adversity, and accomplishing my goals in spite of setbacks. There’s a sign on the school near my home that reads: “Achievement doesn’t let traffic get in the way”

Like yours, most of my childhood was spend indoors. We had an old piano in the basement, so I learned to play and discovered I really liked it. I am still playing and having a ball with it!

So I went to college in biology. Girls weren’t supposed to be smart, so that was difficult also. The chairman of the biology department was a plant ecologist. One of the “required” courses was plant taxonomy. I spent the whole semester out in the fields and woods identifying plants. What an adventure! Sometimes I wore a ski mask, sometimes other students would bring back plants for me to identify in the lab. For some reason, I didn’t do well in that class – go figure!

The rest of college was uneventful, I did well and graduated in 1966. The graduation ceremony was outdoors (!). So I couldn’t go – another in the long line of events I couldn’t attend.

After college, I got a Master’s degree in radiation biology (it was the Cold War) and then went to work for a pharmaceutical firm. I worked there for several years, then got a new job at Columbia University where I met my husband-to-be, a resident in pathology. Living and working in New York City was a new experience in freedom for me. The tall buildings effectively gave me a place to walk even during the day! We explored everywhere, walking miles each weekend.

I worked several years as a technician in the Pathology Department at Columbia, then left to enter graduate school at Cornell University (also in New York City). This was in the mid-1970s, and I finished my PhD in immunology in 1979. My husband had to enter the Navy, since he was deferred during the Vietnam war. I took a post-doctoral position at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, MD. We had a wonderful time working and exploring the nearby countryside as well as Washington, DC. This city was an entirely new experience. No tall buildings, no public transportation, it was hard for me to get around. Fortunately, my husband didn’t like the sun either, so we did woodland hikes, cavern exploration and anything else that kept us covered.

Around 1981, I diagnosed myself by searching the medical literature. The diagnosis was quickly confirmed after a skin biopsy by my dermatologist. I knew there was danger of liver failure, but according to reports, the majority of those occurred in childhood. I was already in my 40s, so I thought I had dodged the bullet. Alas, it was not so.

In 1988, I started to feel tired and started to lose weight. Felt increasingly awful late in the year. When I finally saw my doctor, I was diagnosed with liver failure that was pretty far advanced. Since I’m never one to give up, I had worked all through the early symptoms and was in aerobics class two weeks before my transplant. I crashed in late January 1989 and was sent to Pittsburgh by ambulance to wait for an organ. I got a liver in mid-February, just nine days after I was listed. Recovered well and went home in two weeks, and back to work in six. Like I said, I’m never one to give up.

The medications for transplant are daunting and dangerous. The biggest risk is immunosuppression. Without a powerful immune system, one is prone to unusual and dangerous infections. I weathered several, including fungal meningitis, hepatitis, cytomegalovirus, to name a few. Kept going. One thing I learned early on was that if I immersed myself in work, I didn’t have time to worry. That strategy has always worked for me, but it’s probably not for everyone.

It’s been 23 years since that transplant, and I’m still going strong. I’ve retired from my day job, am teaching part-time at two local community colleges. Still having fun, learning every day. Since my retirement, I’m playing the piano better than ever, sleeping better than ever, and my house is finally clean [grin].

It seems as if my whole life was spent overcoming obstacles, career, health, education. I’m definitely a stronger person for it, and although it’s been hard, I feel prepared for anything that can come my way.

Here’s a little poem I wrote in a workshop:

Oh, hello again, Death

Back again for another try?

Oh, you’ll win, eventually,

But not today!