Erythropoietic Protoporphyria (EPP)

One of the most satisfying experiences of my life was being diagnosed with EPP in May 2016. Don’t get me wrong - I wasn’t excited to have the disease, but at last I had the answer to a 45-year-old mystery. My older brother and I have both been “allergic to the sun” since the age of three, but we never knew what caused the itching, swelling and burning pain we experienced whenever we spent too much time in the sun.

Hating the Sun:

For as long as I can remember I have been a shy and reserved person. I’m not sure how much the limitations imposed by my sun disorder affected the development of my personality as a child, but I know I was afraid of other people making fun of me when I wore a wide-brimmed hat, long-sleeved shirts and white cotton gloves to protect myself from the sun. The thought of speaking up and telling people that I was “allergic to the sun” scared me, so I either took part in required outdoors activities (like recess and P.E. class) and suffered a painful reaction, or I kept to myself much of the time, resulting in social isolation. On the rare occasion when I tried to stand up for myself and tell an adult that I really couldn’t go outside in the sun, I was accused of trying to get out of doing something because I was lazy or I wanted to ruin a fun activity for the others. Fortunately my family was very good about realizing there were things I couldn’t do, like play outdoor sports, while still trying to provide me with the opportunity to try to do things with the whole family, such as go on vacations.

My tendency to avoid social contact continued through high school and college, when my disorder really began to affect many aspects of my life. Realizing I wouldn’t be able to protect myself from the sun on the practice field, I dropped out of band after 8th grade instead of continuing on into the high school marching band. I usually didn’t participate in activities that would require me to be outside during the day. On the occasions I tried to do “normal” things like go to an amusement park, participate in a junior high school trip to Washington, D.C., or experience the cultures of Germany, Switzerland and Austria on a ten-day trip to Europe while in tenth grade, I always ended up paying the consequences by suffering a severe reaction that sometimes lasted more than a week. At that age not only had I not developed the diligence to always wear appropriate sun-protective clothing, but I also didn’t really know what kinds of fabrics would keep me safe.

You would think that after years of getting “sunburned” that I would have learned my lesson about trying to do things that would put my skin in danger, but when I was a senior in college, I began an eleven-month study abroad program in Germany and Austria. Four days into the program I suffered the worst reaction of my life while making the 20-minute walk back and forth between my dorm room and the language institute where I was studying. Three days later, after realizing my dream of living in a German-speaking country wasn’t going to work out, I was on a airplane headed back home. That was a wake-up call that I would need to make major changes in my lifestyle.

During the next thirteen years I allowed my inability to go into the sun to influence what I could and couldn’t do. As I continued pursuing studies in choral music singing and conducting, I passed up on joining certain choirs because I wouldn’t be able to go on tour to the U.S. East Coast, Florida, and Europe. As a new teacher I wasn’t able to take my choir students to DisneyWorld or other fun destinations because I knew I wouldn’t be able to chaperone my students if my skin were swollen and burning. I let this disease rule my life.

Taking Back Control:

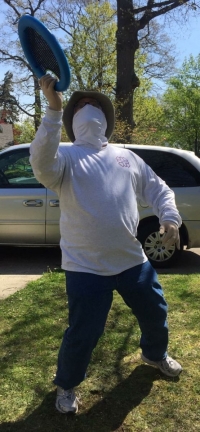

By the time I reached my early- to mid-thirties I realized I was tired of foregoing activities I really wanted to take part in. I was finally ready to wear adequate sun protection apparel, including a wide-brimmed hat, long-sleeved shirts or jackets, long-pants, and if absolutely necessary, the dreaded gloves. This would allow me to spend time outdoors with my domestic partner Michael and to pursue graduate courses in, of all places, Las Vegas (with its endlessly sunny days and 110-degree temperatures in July). I also realized that if I explained that I couldn’t go outdoors unprotected, the kind of people I really wanted in my life wouldn’t make fun of me. Since 2002 I’ve been able to vacation in places such as Chicago, Florida and Washington, D.C., without having a reaction. I had finally learned how to manage this disorder, and I haven’t had a severe debilitating reaction since then.

Making an Exciting Discovery:

Over the years I wondered what caused my severe reactions to the sun, but no one was able to give me an answer, not even the dermatologist I saw a couple of times during my high school years. Every once in a while, out of curiosity I would search online for terms such as “allergic to the sun” and “sun allergy,” but I never found anything that resembled the symptoms I have. In October 2015, however, I found a link to the ABC News story that featured Savannah Fulkerson, an 11-year-old girl with EPP. As I discovered more sources about the disease, including the NBC Dateline episode “Out of the Shadows” and the website of the American Porphyria Foundation, I grew more convinced that I had EPP.

Through my research into EPP I knew that it can often be difficult to not only get the correct lab work ordered, but also to get that work done correctly. After six months of weaving my way through a chain of physicians, including my primary care physician, a dermatologist, and a hematologist, I was finally able to meet with Dr. Angelika Erwin and her assistant, Allison Schreiber, at the Cleveland Clinic. It was a relief to not have to go to an appointment with a stack of papers about EPP and tell the doctor, “I know this is going to sound weird, but I believe I have a rare genetic metabolic blood disorder called Erythropoietic Protoporphyria, and here are the tests I’d like you to order.”

While I wish I didn’t have to worry about the amount of sun exposure I get, whether I have my sun protective clothing and gear with me at all times, and how I’m going to look wearing it, it is a relief to know that I have an actual disease that I can tell people about, instead of giving what seems like a lame explanation that I “can’t go out in the sun.” I have lost track of the times when people thought I was faking my illness in order to get out of doing work outdoors, or that I wanted to get special attention by wearing long-sleeves, a wide-brimmed hat and gloves in 90-degree temperatures. (Yes, I really want people to point and stare at me.) When I was younger it was emotionally hurtful to find out that people talked behind my back, saying that my sun allergy was “all in my head.”

Making contact with other people with EPP through the American Porphyria Foundation’s Facebook pages has truly been a blessing for me. Although I wish that none of us had this terrible disease, it is comforting to know other people who understand what I go through on a daily basis, as well as rewarding to be able to provide support for others with EPP. I look forward to the day when Scenesse® (afamelanotide) is available as a treatment for adult patients of EPP in the United States, and for testing to begin on children so that they can gain access to this treatment.